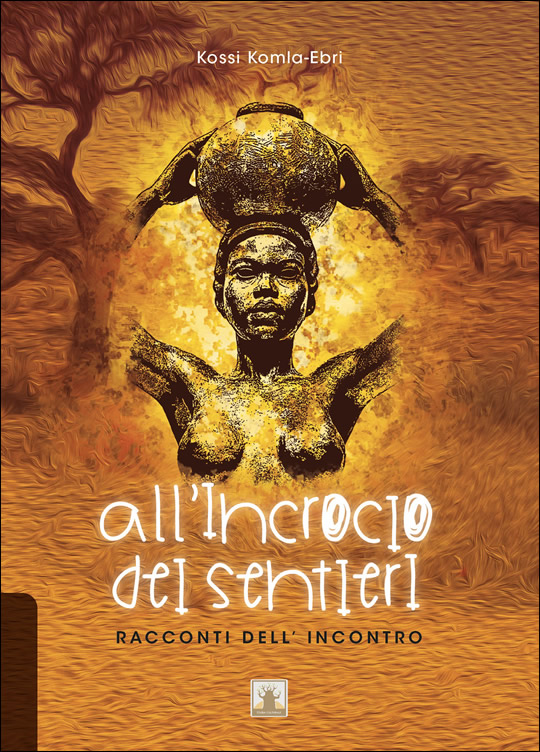

Kossi-Komla-Ebri

all'incrocio dei sentieri

RACCONTI DELL'INCONTRO

Prima edizione

2003

"All'incrocio dei sentieri" - Edizioni EMI

Seconda edizione

Ottobre 2009

"All'incrocio dei sentieri" Racconti dell'incontro - Edizioni dell'arco

Terza edizione

Maggio 2018

All'incrocio dei sentieri" Racconti dell'incontro - Edizioni TOUBA CULTURALE ITALY srl

via Cesare Battisti 1b 20854 Vedano al Lambro (MB)

toubaculturaleitaly@libero.it

+39 3804788847

Progetto grafico e impaginazione:

Alessandra Carcano

Stampato in Italia 2018

proprietà letteraria riservata

© Touba Culturale Italy srl

www.toubaculturaleitaly.wordpress.com

È vietata la riproduzione, anche parziale, con qualsiasi mezzo effettuata, compresa la fotocopia, anche ad uso interno o didattico, non autorizzata.

PREFACE

Refined and intense narrator, capable of interpreting in his works the sense of social grayness and belonging to his desolate time, Kossi senses in himself a profound conviction: that according to which the individual is not a self-sufficient entity.

Instead, it is an intentional, defensive entity: an entity, that is, which, due to its constitutive deficiency, tends precisely to project itself out into the context of the world. The other is an indispensable contact person, the "sine qua non" partner of the one. It is the generative source of existential offers and challenges. It is the occasion for adventures and variously maturing events. It is the primary stimulus of its cognitive and affective functions: of the potential and latent ones no less than those already awake and operating. Kossi, through short stories (At the crossroads of the paths), stories (Life and dreams), descriptions of the ancient rites (The bride of the gods), and embarrassments (Embarrassments and New embarrassments), splendid play on words on everyday embarrassments, a real thesaurus of anecdotes, which usually do not exceed the length of a page, urges us to reflect daily.

The other, especially black, with its ways, sounds, colors, rituals questions us at a level of radical depth, gives us back the terrible sensation of our contingency, refers us to the possible accidental nature of who we are, of what that we care about, reminds us in the middle of our life, even when the end is far away, our unsurpassed finiteness of species, collective, individual.

Much of our intellectual ability is destined to stifle this feeling, to cancel the risk that comes to us from the perception that other points of view on the world are possible.

Without the other, without the encounter (- confrontation) with the "others", this complex awakening, mobilization and development of the human components (psychic, rational, relational) would not occur (as sometimes unfortunately happens), or would occur to a very large extent limited. In summary: the other way to discover the self and, above all, to build the self. In fact, only the existence of otherness makes us discover the property deemed most personal and private: our own identity. In his texts the circumscribed and fugitive episodes are transformed into a rhythmic-narrative measure which, through flashes of colors, contrasting, reflections, attest with a dry language that knows how to be moved and at the same time self-deprecating, a firm expressive autonomy, that of "writing of mourning ".

Now the chorus prevails over the subjectivity, now the motifs support the structural action of his works: in all of them we find the texture of the voices of orality, or as Kossi himself defines it, of the "oraling".

In the short and flashing sections there is, in addition to the lyrical lighting, the anxious curiosity of those who are quick to grasp, in the incessant passing of the days, a new passage towards the occasion that can reserve a thrill: the figure of the irony...

Writing not only of suffering and discomfort, but above all writing of hope. There is an invitation, a concern that is felt between the lines of his narration, for a world that needs to be recomposed, for a mentality that needs to be changed.

Promoting this culture is the commitment of the writer Kossi Komla-Ebri.

Cosimo Laneve

Dean of the Faculty of Education

University of Bari

"Home...sickness"

Kossi Komla-Ebri

Out of all the years I’ve spent in Italy, I wouldn’t know which ones to blame for what’s happening to me now. I know very well that I should decide once and for all to cut the umbilical cord that binds me to this bad habit, this sort of sickness.

I can’t even remember how it all started, surely with my return to Africa from Italy.

“Italy!” In those days just thinking about it was like touching the sky. For years Fofo (my brother) had been promising that he’d take me to Europe with him. I don’t even know how to describe the immensity of my joy when that long-awaited letter arrived. My cousin who lived in the city brought the letter to us, since his mailbox served as the refugium peccatorum [sanctuary] for all of the correspondence from our relatives and everyone else in the village.

My father was a little hesitant to let me go.

“A girl traveling to the whites’ country all by herself! Don’t even think about it!”

My mother took my side.

“She’s not going alone, she’s going to meet her brother!” As for the “Don’t even think about it” repeated by her husband, she nodded to me to leave the room, and that nod made me take heart because I knew, appearances aside, who “wore the pants” in our house.

In fact, the next day my mother took me to the market to buy a suitcase, some second-hand slacks, and my father went to town to get all the necessary documents for the trip.

The night before my departure I saw tender tears mark my mother’s face and I had a fleeting sense of guilt, knowing that I was leaving her alone to do all the work in the fields and the house. Papa withdrew into a defensive silence until the last moment, then, when telling me good-bye, he put a talisman of inlaid leather into my hand with a shell and muttered, “Take care of yourself!”

Italy! God, the cold! I never imagined it could be so cutting. My lips chapped, my fingers froze, and my skin took on that gray color of a lizard, though I slathered myself with coconut lotion. The first night was infernal, I spent it in a hotel in Rome where my brother had made a reservation for me: lying in a bed that I would have used for matting in my cottage, I was half-frozen, not knowing that I was supposed to crawl in between the sheets. Fofo explained it to me the next day and laughed at me, when he came to get me at the station in Bergamo.

My brother had sent for me to look after his house and children because he and his wife both worked all day. He, his Italian wife, and their two children lived in Torre Boldone, a little town not far from Bergamo, where he worked as a doctor. They had prepared a room for me in the basement of their house. It was obvious that they were doing well, even though I found that my brother was a little hen-pecked by his wife, who was the one in charge, just like my mother only more overtly so.

At first it was difficult to communicate with my sister-in-law and niece and nephew because I couldn’t understand the language and my brother refused to act as translator. He immediately instructed me to keep my room clean, to wear the “house skates” when I went into the living room, not to take a shower every day because the heating costs were high, not to leave the lights on over the stairs or in the bathroom, not to take three hours to finish the ironing, not to speak our language, and to keep the volume low on the “funeral dirge” of African music. Included in this list of holy commandments there was the prohibition on preparing foods that took too long to cook and especially foods that filled the house for days with the aroma of spices (“that stink”).

I felt that I was always agonizing over my faux pas like crunching on the bones during a meal, something that my brother loved to do back home. But who knew why it was that here seemed to call up some sense of shame for him. I didn’t know my brother any more, he let his children call him by his first name as if he were their playmate. He and his wife gave them their way in everything, and they even had to beg those kids to eat meat! They were too spoiled. Myself, for my children (I wanted to have at least six), I would raise them as we do in Africa: teach them obedience and respect. I didn’t like how children talked back to their parents.

I smile now thinking about these things, at my shock when I first saw my nephew put on one of his hysterical scenes because a “little skin” had formed over his milk. When I saw my brother get up I was happy, thinking of the well-deserved smack he was going to give the boy, but instead, he simply took a spoon to remove the skin and implore the boy, “Come on, sweetie, just drink a little more!”

I was completely horrified!

I had to take care of those kids, but I could not get them to mind me. One day when I was beside myself, I screamed at them in my language because it was easier for me and they burst out laughing, literally aping my “talk African” with “Abuga bongo bingo!” “And yet,” I thought bitterly, “this is the language of their father’s fathers!” But I didn’t say a word to them.

I didn’t know how to act anymore. My sister-in-law made me feel like an intruder, she watched me with an air of suspicion because, out of politeness, I never looked at her in the eyes when I talked to her. One day I heard her tell a friend on the phone that I was sneaky and hypocritical.

My dream of Europe was mutating into a nightmare, too cold, too little time, and then the indifference, the loneliness.

I spent more and more time locked in my room to cradle myself with memories. I quickly used up the sack of cassava flour and peanuts that my mother had slipped into my suitcase. I couldn’t adjust to always eating pasta: even though they said there was a difference between tortellini, bucatini, spaghetti, and lasagna, but for me it was all pasta. I wanted to taste la pate (white polenta without salt) with a hearty sauce of gombo and chicken with a lot of hot pepper in it, taste it with my hands, take smoking hot handfuls, mince it well, roll it into a ball and press a deep indentation with my thumb in order to easily gather up all the sauce before swallowing it, then lick my fingers deliciously and crunch on a piece of bone.

I smile today at my shame when my body first saw the moon there and I didn’t know what absorbent pads were (I’d brought pieces of cloth with me), or the first time I had the adventure of buying stockings, not knowing that they came in different sizes, colors, and prices.

I still see now, as if it were yesterday, the alarmed face of my sister-in-law when she saw me pull my first attempt at doing laundry out of the washing machine – sweaters that were knotted up and white shirts and underwear that had turned pink or were spotted with purple.

I owe my survival to Conception, a Filipino girl who worked as the housekeeper for the family in the house next door to ours and who spoke a little French. We first saw each other from our balconies while I was trying to beat a carpet, then we met doing the shopping at the supermarket. She’d been in Italy for the past five years and her friendship and her advice were like manna in the desert for me.

I quickly learned to cook and keep the house better. I’d work quickly so then I’d have time left over to read or watch TV. I learned very quickly to appreciate the food. I tried to assimilate as much as possible, to completely forget who I was. With time I became more demanding. I wanted my brother to let me go out every so often, I wanted my day off, just like Conception, I wanted the money to send a present to my mother or to buy clothes that I liked and not just take my sister-in-law’s hand-me-downs. In the arguments that were born out of this, my brother and I exchanged reciprocal accusations, that I never would have thought I could formulate. He said, “You are ungrateful!” when I told him that I’d found a place working for an elderly woman in Bergamo, because I wanted to be independent. At first, he’d shout, “If we’d wanted to pay for a babysitter or housekeeper we didn’t need to bring you all the way from Africa, you know!” then when confronted with the firmness of my decision, he played the sentimental card, “So you don’t care that you’re leaving when we need you, you’d abandon your niece and nephew, you only pretended to care about them! You are completely heartless!”

I alone know what it cost me to leave my brother, resisting the temptation to embrace him, trying to explain to him that I could not come all the way to Europe without at least trying to accomplish something; unlike him, I dreamed of going home someday and creating something of my own, that I didn’t want to be a servant an entire life in a foreign country.

So one spring day when the morning air stung my face and nostrils, and nature was rising from her dark lethargy with the sprouting of the plants and the birds’ sweet song of freedom, I made my flight toward independence. I went to live just outside of Bergamo with an elderly lady (Maria) who cleared my residency with the police and got me all of the documents to stay in the country legally. Meanwhile, I got enrolled in a sewing course and saved my money in order to buy a sewing machine all my own.

After the first period of anger passed and after a letter from our father, my brother came to visit me unbeknownst to his wife. There at my new house, I found again the Fofo I had always known; we spoke our own language, I cooked our food for him, hot and spicy, which he swallowed greedily… with his hands, then he snapped bones with his teeth and sucked out the marrow, making an infernal noise, and I even heard him laugh as we do at home, a belly laugh, and talk, and remember people and events from our village. One day watching him let loose and dance to the rhythm of our traditional music, I laughed at him, “Doctor, if your patients could just see you now!”

And he responded, laughing, “They would say, ‘And yet you seemed like one of us!’”

Then he left with a light heart and with the ironic glint in his eye of someone who had fun betraying himself.

My friend Conception came to visit me every other Sunday and together we’d fantasize about all the plans we wanted to accomplish once we’d returned home permanently. My idea was to start a co-op of tailors and make European-style clothes with African fabrics, maybe even to sell to the big distributors in Europe…

I also had the opportunity to meet other co-nationals and so I started greeting the other Africans that I met on the street. Some came to visit me, because I was lucky enough to have my own apartment on the first floor of the house where we could be together and braid hair, listen to music without disturbing anyone, talk out loud. Our meetings were my only chance to show off my flashy bubu.

Signora Maria was truly kind. One night while we were embroidering the thousandth doily and as I bent over the lace pillow with tired eyes, she confided in me that we had brought the light and the joy of living back into her house even though initially, seeing us talking and gesticulating from far away, it seemed that we were fighting.

One day Fofo found me at home with some of my girl friends absorbed in dancing to a piece of music from our country. When he arrived, a silence fell out of respect but also full of reproof because many considered him to be a “traitor.” Not so much because he’d married a white woman, but because, they said, he’d become like the whites: cold and indifferent toward his people, as if he were ashamed of his origins, and then no one understood why, with all the room that he had in his big house, he never organized an occasional evening to dance at least on the important holidays. He felt uncomfortable and after a little while he ran off with the excuse of needing to see a patient. From then on, he started to call me before stopping by, as they do in Europe. I’m not defending him, but I understood that he had made the choice to stay permanently in Italy and to keep peace in his family, he had to stoop to making personal compromises.

Knowing my sister-in-law, I understood that he couldn’t bring “people” home with no warning as we do at home, and invite them to lunch or dinner or even to spend the night. Here everything is different. At home, being used to big families and the fact that we eat just one course, usually with a sauce for a base, then it’s easy to heat up a little more, or to stir some pate in a pan or crush up some fufu to make room for one more guest around table. Some people blamed my sister-in-law, but I believe that the pace of life here is such that time dilutes feelings, devouring life and people. And if it was fine with him like this, as he confided to me one day, it should be fine with us, because he claimed the right to live his life as a free individual and not as part of a collective as African solidarity required, and besides, he didn’t feel obligated to associate with someone simply because that person was black or came from Africa.

“Here in Europe,” he pontificated, “everyone must think of himself, end of story. I only feel a duty toward my close relatives and only if they are in need and are deserving.”

Clearly, I didn’t share his point of view. I only replied, “Fofo, this country, this fog, it’s not for me. I miss the sunshine, the holidays in the village, the weather, people’s laughter, living together with others.”

And still, I went on working, saving, suffocating my homesickness with one single thought and goal: returning home and opening my tailor shop.

Finally, two years ago, with a knot in my throat I embraced Signora Maria, who had been so good to me, knowing that my departure corresponded to her entering a home. Holding back my growing tears with difficulty, I said good-bye to my brother, Conception, and all my friends and I went “home” with my suitcase full of gifts, plates, and silverware, and a dream to fulfill.

After returning to Africa, the first week effervesced and I understood that I could no longer live in the village where there were no lights and no running water, as I had become used to certain conveniences. I could no longer even start a decent conversation with my girl friends from before; by now they had gotten married and some already had two or three children and I felt that they maliciously envied me. My aging parents insisted that they wanted to choose a man for me to marry, but I had already decided on the liberated life of a single person; I didn’t want to be any man’s servant and even less did I want to give up my plans.

I decided to move to the city, partly to avoid the daily assault by swarms of relatives who came begging, and partly because the heat, the flies, and the mosquitoes had become unbearable to me and I needed to live in an atmosphere that was air conditioned, clean, and calm.

The first year was not very easy, but slowly I managed to build up a steady clientele and one of my clients, Sonia, who had her hair styling salon opposite to my shop, had become my best friend. Sonia is a shapely girl, nice and determined; she returned from Germany where she’d worked “in show business” and came back to invest all of her savings in her salon.

Now things are going better for me.

Honestly, I would have to say, things would go even better for me now if it weren’t for this strange sensation of restlessness that every now and again invades me down to my very bones.

Then I take my car, I go downtown and look around the shops, I go to the grocery store and buy some spaghetti, some cans of tomatoes, some meat imported from France, some taleggio cheese, then I go home to cook it all up and invite Sonia to come and have dinner with me. Sometimes we go to have a cocktail at the “Gattobar” and then we rush out to devour a pizza “Da Silvia” and to conclude the evening we go see some nice movie starring Mastroianni and Sofia Loren. Or sometimes we stay at my house and look at all of my photos from when I was “home” in Italy, listening to the songs from the Festival of Sanremo, the music of Baglioni, Ramazzotti, or Zucchero.

Sundays, I cross the whole city to attend mass in the parish with the Combonian missionary priests so that at the end I can talk with them a little in Italian.

Sometimes it’s Sonia who invites me to have a beer at the “Baveria,” the tavern for the German sailors, whom she astonishes with her perfect German, then we go to her house to eat sausage with sauerkraut and mustard and dance Viennese waltzes.

I don’t know how to explain this weakness, this mania that I can’t seem to get rid of, and which even makes me root for the Azzuri when there is an international soccer match. Once after an Italy vs. Germany game, Sonia and I didn’t speak to each other for a week.

Ah, Italy! To think that in Italy I wanted so much to go home! Now I feel like a tenant in two countries: sometimes I’m happy for that, sometimes I feel divided, a little unbalanced, as if a part of me remained there, and yet I know that there I would still have suffered from “mal di Africa.”

Maybe it’s just nostalgia, or more simply, “mal di… mal di Europa.”[i]

Translated by Marie Orton in "Multicultural Literature in Contemporary Italy" Edited by Marie Orton and Graziella Parati-Fairleigh Dickinson University Press-Madison.Teaneck 2007

[i] The term “mal d’Africa” was used by Italians to express nostalgia for a colonial life, or for the exotic life they had in Africa.