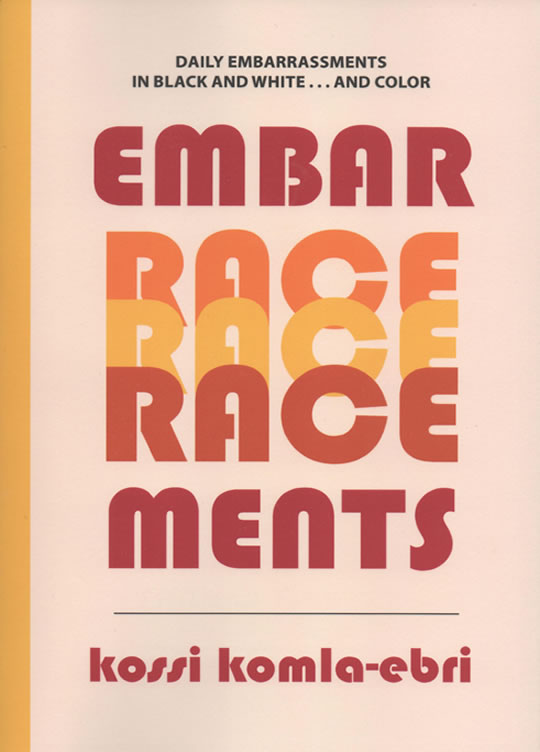

EMBAR RACE MENTS

Daily Embarrassments in Black and White . . . and Color

Kossi Komla-Ebri

Translated by Marie Orton

Bordighera Press

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019943037

© 2002 by Kossi Komla-Ebri

© 2004 by Kossi Komla-Ebri

English language Translation © 2019 by Marie Orton

EDITOR'S NOTE: In Italian, the terms “nero,” “negro,” and “persona di colore” do not have exact equivalents in English. “Negro” is considered derogatory and racist. Though in most contexts, “negro” is not considered as offensive as the English “nigger,” it can sometimes function synonymously. The usage of “di colore” in Italian was originally borrowed from English as an attempt at political correctness, but is now considered a racially charged term.

While “nero” is the most accepted racial descriptor, Kossi KomlaEbri’s stories point out that it, too, can often carry a racist taint. For these reasons, we have at times opted to keep the original Italian word in this volume to best reflect the various nuances of meaning.

All rights reserved. Parts of this book may be reprinted only by written permission from the author, and may not be reproduced for publication in book, magazine, or electronic media of any kind, except for purposes of literary review by critics.

Printed in the United States.

Published by

Bordighera Press

John D. Calandra Italian American Institute

25 West 43rd Street, 17th Floor

New York, NY 10036

Crossings 24

ISBN 978-1-59954-124-2

CONTENTS

Introduction by Graziella Parati

Preface by Cécile Kyenge

I. Daily Embarrassments in Black and White

19 “Hey, bel negro, do you want to make a few cents?”

21 Geography Lesson

23 Babysitter

25 Rush Hour

27 Ethnocentrism

29 The Color of Money

31 “Excuse me, are you Italian?”

33 “Please connect your mouth to . . . your brain”

35 Back to the Boss

37 Big Chief Carlo

39 No One is Deafer

41 “Who’s Afraid of the Big White Man?”

43 The Move

45 “Mogli e buoi dei paesi tuoi”

47 The Voice of Innocence

49 Just a Joke

51 Reasons to Hope

53 Vu cumprà Syndrome

55 “Knock and it shall be opened unto you”

57 Quid pro quo

61 Things are the Same All Over

63 Euphemisms

65 Vu cumprà Mania

67 Common Usage

69 Other Cultures

71 Multiculturalism and Shame

73 “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?”

75 Identity

II. More Embarrassments in Black and White . . . and Color

79 I. Q. Test

83 Goodness

85 Hypersensitivity

87 An Extra Place at Dinner

89 Woes of an Attendant to the Elderly

91 Good Manners

93 Waiting for the Bus

95 The Boss’ Bread

97 No One

99 Faux Pas

101 Lucy’s Children

103 Double Fear

105 Everywhere You Go

107 Lucky

109 Sibling Rivalry

111 KKK

112 Mi casa es su casa

115 Integration

117 Peace March

119 Negritude

121 Love One Another, or Better Yet: New Times are Coming

123 Black Christmas

125 Revenge

127 A Grandmother’s Love

129 “Parla ‘me ta mànget”

131 Fruttaids

133 The Color of a Soccer Fan

135 The . . . Black Sheep

137 Innocent Curiosity

139 Cell Phone

141 Strange Love

143 Biological Children, Adopted Children

145 Italianness Test

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND TRANSLATOR

INTRODUCTION

I met Kossi Komla-Ebri in 1997. It was June, and I was present at the awards ceremony of the Eks&Tra literary prize for immigrant writers, the first award of its kind in Italy. Kossi is a well-known medical doctor in Northern Italy who left Togo to attend medical school in Bologna, and, to his great surprise, he was one of the prize winners. He arrived accompanied by his wife and his children who had played a major role in his success. They had seen their father scribble away in his spare time and had been the ones to submit his short story. They gave him the great gift of visibility as a writer and the motivation to continue writing.

Writing started as a secondary passion that has, however, turned Kossi into a public intellectual who leverages paradox in his writing and in his political career. He lives in a very conservative region of Lombardy, dominated by a nationalist and populist party known for its misogyny and xenophobia. A few years ago, he became the candidate for a moderate center-left party that had little chance to win the election. Kossi used provocation in order to strategically challenge the conservative apathy of local voters. His round black face dominated the surface of his political posters hanging all over the city, and he designed swag to be distributed at his political rallies. The free gifts were small glass bottles filled with olive oil, meant by Kossi to invoke the name of his coalition party, L’Ulivo. The labels were smaller versions of the election posters sporting a close-up of his face.

Because olive oil is immediately recognizable as a symbol of Italianness and belonging, Kossi’s swag thus disseminated his identity as an Italian by superimposing his difference (his face) over a stereotypical Italian product (the olive oil). No matter which political party one belonged to, the reaction to this “gift” was laughter at this playful acknowledgement of what seemed to be a paradox twenty-five years ago: an AfricanItalian politician. It was a provocative statement coated in humor that transformed him into a local celebrity. It was also the beginning of his career as a writer who embraces humor as a powerful weapon against the troubling and ever-increasing racism in Italy

IMBARAZZISMI

Pirandello teaches us that an event provokes laughter when it is a deviation from the norm, a change from what is expected. He uses a rather misogynist example to explain his point, but I usually tell my students that if I were to stumble and fall in front of them during a class, they would probably react instinctively by laughing. It is unexpected and hence comic. However, concern would probably replace that initial laughter. The event would not be comic any more if they were concerned for my well-being. If it then turned out that I was uninjured, my clumsiness could still be humorous when they related my fall later to their friends. Humor is, for Pirandello, an intellectual reaction to the deviation from the norm which is colored with compassion and understanding, and is very different from instinctive laughter. Humor permeates Pirandello’s work and exposes the intricacies of life and the human psyche. It is humor that allows writers to create narratives that politically engage the world around us.

Kossi Komla-Ebri’s work filters his disappointment with the nationalistic and xenophobic sentiments that dominate the world in which he has lived for longer than three decades through a special kind of humor that powerfully exposes the absurdities of racism. As an educated black man, he is the right individual to show us that racism works as a weapon aimed at any embodiment of difference and crosses all social classes. Kossi’s autobiographical narratives examine through humor how he, despite his education and social contributions, is still the target of racist attitudes that attempt to subsume him into the same faceless stereotypes assigned to all black immigrants. It is in fact the difference of the immigrant body that people want to discipline and erase. Bigotry undermines any rational discussion about the economic advantages that migrants bring to a country like Italy.

We do know that there are more Italian citizens leaving Italy and more migrants coming into Italy. Instead of considering this phenomenon as a balancing act, many Italians want to marginalize the latter and make them invisible. However, it has been well-established that migrants bring skills and abilities that would be very useful for the country as a whole. Nevertheless, many who define themselves as Italians see all immigrants homogeneously as “black,” no matter the color of their

skin. The issue is never the singularity of the individuals who move and migrate. Dominant discourses treat them as one burdensome mass. Foryears, politics have increasingly embraced such absurdities. Politics have replicated and disseminated such discourses.

Kossi’s narratives intervene in order to interrupt the dominant racist rants through humorous short stories that demand reactions from the readers. And Kossi’s stories can’t help but provoke a reaction. For example, the volume’s first anecdote, “Hey, bel negro, do you want to make a few cents?” the protagonist is in the supermarket parking lot helping his (white) wife load the groceries into the trunk of their car. He then walks back toward the supermarket to return the cart. In Italy, supermarket carts are chained together in order to prevent their theft. A customer inserts a one-euro coin to unlock one cart and the coin is returned when the cart is brought back. On his way back to the carts, the protagonist encounters a native Italian man who motions him that if returns his cart too, Kossi can keep the refund of the one euro.

For the Italian man, interracial couples are an unconceivable concept. Indeed, if they even do exist, then the black member of the couple must be the disadvantaged one, the one inevitably in need of charity. This mindset is the norm for this native Italian man, as he is blind to the pervasive presence of diverse couples in Italy. Kossi’s actual situation deviated from this perceived “norm” and makes the story humorous at the expense of the bigoted Italian gentleman. After returning to the car, the protagonist tells his spouse what happened and at subsequent trips to the supermarket, they re-enact together this same moment as a pantomime and inside joke. The humiliation of the original encounter is transformed into humor as it is performed in this space of mutual understanding.

Frequently in these stories, alongside the humor, the protagonists’ pain and humiliation remain undiminished. This juxtaposition heightens the feeling of indignation in the reader. Kossi’s short stories demonstrate the extent to which diversity is a social construct. In laughing at the racist Italian man at the supermarket, we laugh at socially created prejudices that must be dismantled because they disseminate and perpetrate the marginalization of others. Kossi’s sorrow, anguish, and heartache may be coated in humor, but they are there on the page to be understood.

So what are we to do? How can we combat racisms that have become so normalized? This book itself is one answer. Kossi and other writers have given us the tools to fight. Let’s take this book and let’s circulate it. Let’s make sure that all libraries have a copy, and read it to our children and

grandchildren. Let’s volunteer to read it in schools, in Sunday school, at special events in bookstores. Let’s broadcast a new norm grounded in equality and inclusion.

Graziella Parati

Paul D. Paganucci Professor of Italian

Dartmouth College

Preface

Ogni nero che vive in Italia ha un proprio ricco repertorio di «imbarazzismi». Questo fortunato neologismo, ideato da Kossi KomlaEbri, sta a indicare situazioni che non rientrano nei casi di discriminazione crudele, violenta o quantomeno intenzionale, ma si tratta di episodi di razzismo di piccolo calibro, che avvengono senza che il loro autore se ne sia reso propriamente conto.

L’imbarazzismo, come una gaffe sconveniente, crea disagio. Come un lapsus freudiano, svela giudizi e pregiudizi rimossi. Ma per quanto ciascuno di questi episodi non sia grave, gli imbarazzismi feriscono le loro vittime, perché sono quotidiani e perché illustrano una mentalità diffusa popolata di stereotipi.

Come superarla? Il primo passo per sconfiggere i pregiudizi è quello di saperli riconoscere. Bisogna ammettere che ciascuno di noi ne ha diversi, quindi dobbiamo imparare a vederli e poi essere disposti a rivederli, ampliando le nostre conoscenze e mettendoli a confronto con la realtà dei fatti.

Questa raccolta di aneddoti divertenti, amari e folgoranti ci aiuta a smascherare l’etnocentrismo e gli stereotipi con ironia, un’arma gentile ma efficace contro il razzismo latente.

Il volume del medico-scrittore italo-togolese ci rammenta che dobbiamo fare ancora della strada per costruire una società e una cittadinanza veramente inclusive nei confronti delle minoranze e verso le persone di diversa origine, ma dobbiamo anche constatare che la mentalità sta cambiando ed in parte è già mutata.

La società italiana è in rapida trasformazione: tra i protagonisti delle brevi storie collezionate da Kossi Komla-Ebri – oltre a persone che sono ancora disorientate da un’Italia sempre più meticcia – vi sono molte coppie miste, famiglie adottive, gruppi di amici costituiti da persone di nazionalità diverse. Vi è insomma un Paese per cui nei legami d’affetto e nei rapporti civili il colore della pelle, al pari del colore dei capelli, è solo questione di melanina. Un Paese dove le differenze di ogni consociato sono un potenziale di cui farne tesoro.

On. Cécile Kyenge

Ministro per l’integrazione

Every person of color living in Italy has his or her own rich repetoire of “embar-race-ments.” This astute neologism coined by Kossi Komla-Ebri serves to describe situations that don’t enter into the category of violent, cruel, or even intentional discrimination, but are more those episodes of small-caliber racism, episodes that occur without the perpetrator even realizing it.

An “embar-race-ment,” like an offensive faux pas, creates uneasiness. Like a Freudian slip, it reveals repressed judgements and prejudices. And while each of these episodes might not be considered serious, “emba-race-ments” wound their victims, because they occur daily and because they illustrate a common mentality that is packed with stereotypes.

How can this mentality be overcome? The first step in defeating prejudice is to know how to recognize it. We must admit that each one of us has our own prejudices, and we must therefore learn to identify them and be willing to re-evaluate them, widening our understanding and measuring our prejudices against factual reality.

This collection of comical, acrid, and razor-sharp anectdotes helps us to unmask our ethnocentrism and stereotypes with irony, that gentle but effective weapon against latent racism.

This volume by the Italian-Togolese writer and practicing physician Kossi Komla-Ebri reminds us that there is still a great deal of work to be done in order to construct a society and a citizenry that is truly inclusive of minorities and individuals of different origins, but we must also acknowledge that the current mentality is shifting and to a degree, has already shifted.

Italian society is undergoing a rapid transformation: the protagonists of these short stories collected by Kossi Komla-Ebri stand in contrast to those individuals who are still disoriented by a multicultural Italy. At the same time, there are also many interracial marriages, adoptive families,

and groups of friends consisting of individuals from many different nationalities. This is a Nation. Thus, in the bonds of friendship as well as in the interactions in civil society, skin color, just like hair color, must be regarded merely as a question of melanin. A Nation where the differences of every fellow citizen can potentially become a treasure.

The Honorable Cécile Kyenge

Italian Minister of Integration

I. Quotidiani imbarazzi in bianco e nero

I. Daily Embarrassments in Black and White

BEL NEGRO, VUOI GUADAGNARTI 500 LIRE?

Un giorno uscivo dal supermercato con mia moglie, italiana. Avevamo fatto spesa da riempire due carrelli. Dopo aver caricato il tutto nel portabagagli, mia moglie mi spinse i due carrelli per recuperare 500 lire.

M’incamminavo con i miei carrelli, quando sentii alle spalle un – Ssst! – , accompagnato da uno schioccare di dita. Mi girai e vidi un signore sulla cinquantina farmi segno con l’indice di avvicinarmi, e abbozzare il gesto di spingere il suo carrello verso di me. Lo guardai con un’espressione che mia moglie descrisse poi come carica di lampi e fulmini.Comunque il mio sguardo doveva essere stato eloquente, perché lo vidi richiamare il suo carrello e portarselo per conto suo. Senz’altro, visto il colore della mia pelle e il gesto della mia signora di affidarmi i carrelli, il sciur aveva fatto la somma: negro + carrelli = povero extracomunitario che sbarca il lunario. Tornando alla macchina, vidi la mia dolce metà, che conoscendo la mia permalosità, si contorceva dalle risate. Mi misi a ridere anch’io. Ora ogni volta che andiamo a fare la spesa, lei mi spinge, ammiccando, il carrello con voce scherzosa:

– Ehi bel negro, vuoi guadagnarti 500 lire?

“HEY, BEL NEGRO, DO YOU WANT

TO MAKE A FEW CENTS?”

One day I was coming out of the supermarket with my wife, a native Italian. We’d bought enough groceries to fill two carts. After loading everything into the trunk, my wife pushed the carts over to me to take back inside.

I was walking back with both carts when I heard from behind me a “Hey! Hey!” and fingers snapping. I turned and saw a middle-aged man motioning me over with his finger and gesturing that he wanted to push his cart over to me. I looked at him with an expression that my wife describes as “thunder and lightning.”

The look must have spoken eloquently because I saw him take his own cart and return it himself.

Obviously, seeing the color of my skin, and seeing how a woman had given the carts to me, the gentleman had made the calculation: “Negro + carts = impoverished illegal alien eking out a living.”

When I got back to my car, I saw my better half (who knows how touchy I am) in contortions of laughter. I had to laugh, too.

Now every time we go shopping, my wife pushes the cart over to me with a wink and says, “Hey, bel negro, do you want to make a few cents?”

LEZIONE DI GEOGRAFIA

Un giorno andavo a scuola di specialità in chirurgia su un treno delle Ferrovie Nord. Ero seduto su quelle poltrone micidiali super riscaldate d’inverno, perciò bisognava discretamente sollevare una natica dopo l’altra per ottenere un po’ di sollievo.

La gente, come al solito, occupava prima tutti gli altri posti e solo quando non aveva più altra scelta, disperata veniva man mano a sedersi nei miei paraggi. Un signore sulla sessantina si sedette di fronte a me e vedevo che già si preparava ad attaccare bottone, per cui mi rifugiai dietro il mio libro, per sfuggire al solito interrogatorio poliziesco con l’uso diretto del tu del tipo: – Da dove vieni? Cosa fai? Di che religione sei?

Questa volta, mi trovai di fronte un «attaccatore» coriaceo, che iniziò con:

– Hello! America?

Risposi con un dignitoso silenzio.

– Capire italiano?

Annuii distratto, ma non riuscii a scoraggiarlo.

– Africa?

Annuii di nuovo pazientemente e lui, prendendo la mia apparente rassegnazione come un tacito assenso, proseguì con la sua inquisizione:

– Tu da che paese Africa venire?

Sentii la mia voce rispondere:

– Togo.

In genere a questo punto, c’è chi dice: – Togo? Sì, ma quale paese? Stato? – oppure nasconde la sua ignoranza dietro un – Ah! –d’intendimento, pensando senz’altro ai famosi biscotti.

In fondo hanno ragione: come si fa a raccapezzarsi di fronte a questo continente balcanizzato con tutti quegli statarelli che cambiano nome a ogni starnuto di un nuovo dittatore?

Intanto il viso del mio perspicace aguzzino, dopo aver aggrottato la fronte in un riflessivo e intenso silenzio, s’illuminò di un sorriso di compassione e con infinita sapienza salì in cattedra:

– Ah Togo! Nel tuo dialetto forse dire Togo, ma noi in italiano dire

Congo. Tu capire? Congo!!

Certo che avevo capito e. . . grazie per la lezione di geografia!

GEOGRAPHY LESSON

One winter day when I was in medical school, I was riding on a Northern Line commuter train in one of those horrible over-heated cars where the only relief from the temperature is to discretely shift weight from one buttock to the other.

As usual, the passengers took all available places farthest from me.

Only when there was no other choice left, out of desperation, someone would come and sit beside me.

An elderly gentleman sat down in the seat opposite. I could see that he wanted to button-hole me, so I took refuge in my book to avoid the ususual police-style interrogation (always using the too familiar “tu” form): “Where’re you from?” “What are you doing in Italy?” “What’s your religion?”

The man across from me was clearly a veteran button-holer.

He started off with, “Hallo! America?”

I responded with dignified silence.

“You talk my language?”

I nodded “yes,” silently but that didn’t seem to discourage him.

"You Africa?”

Patiently, I nodded another “yes,” and taking my resigned silence as a form of tacit consent, he forged forward with his interrogation:

“Where Africa?”

I heard my own voice responding, “Togo.”

Usually at this point most people say, “Togo? Where’s that?” or in an effort to hide their ignorance of African geography, they’ll give me a vague, “Ah!” of recognition, though we both know they’re probably thinking of the Togo brand cookies.

And they’re right. How’s anyone supposed to keep track of an entire conquistator-ed continent with countries that change names overnight with every overthrown government?

After furrowing his brow in intense silent reflection, the face of my perspicacious tormentor lit up with a smile of compassion as he attempted to explain to me patiently,

“Ah, your dialect maybe say ‘Togo,’ but Italian say ‘Congo.’ You understand? You from Congo!!”

Yes, I understood more than you know, and by the way, thank you for the geography lesson!